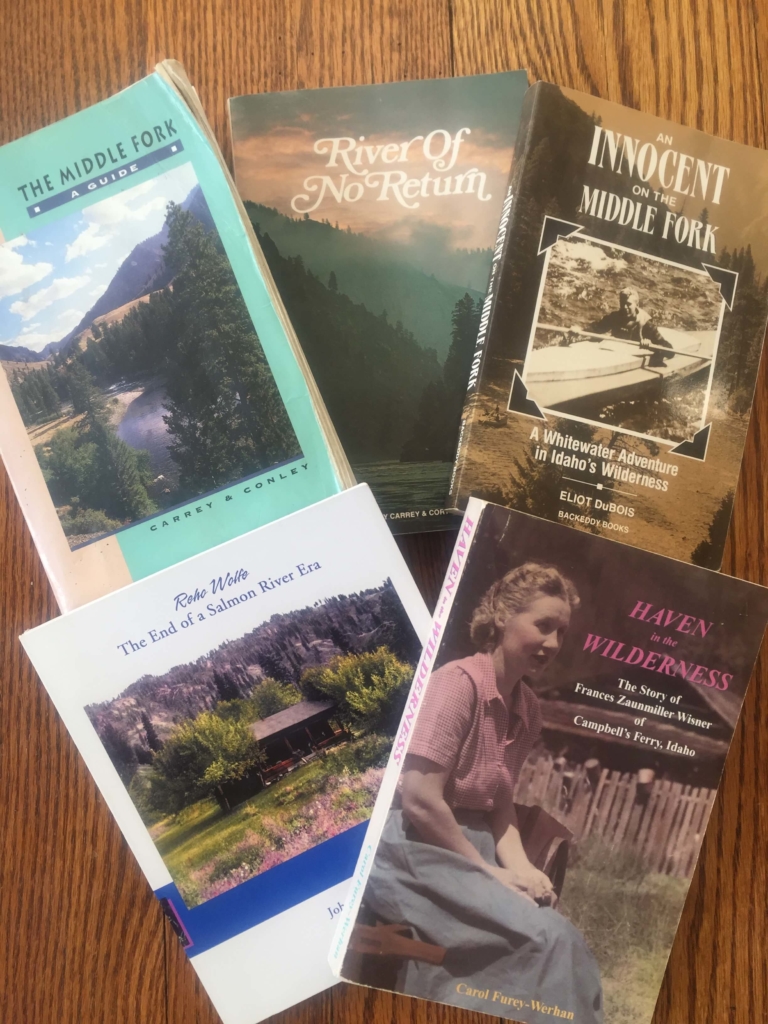

Books about the Salmon River

When I came to the Salmon River 50+ years ago, there were few books about the area, making it difficult to learn about the area. On the other hand, many of the primary sources, such as Johnny Carey, Buckskin Bill, and others were still alive. There has been a trend for people to publish their memories, which has created a literature that greatly aids understanding the back country. Many of these books go out of print in short order, and will be difficult to find. This is not a complete bibliography of Salmon River books, but will at least provide a place to start for people who are interested in learning more about Salmon River country. I’ll add to it as new books are published, as I find others, and as I have time.

One of the earliest books on Salmon River country is River of No Return—R.G. Bailey, 1935 and 1947, 1983, Lewiston Printing, Lewiston Id. Bailey prospected along the Salmon River around 1900, later for many years operated a printing business in Lewiston. He had a strong interest in history of the area, and apparently engaged a young Johnny Carrey in gathering back-country history in the 30s—which led to the Carry-Conley histories of the late 1900s. Bailey is commonly credited with originating the term “River of No Return”—because freight boats built in Salmon to haul supplies into the Salmon River canyon could not return up river, and were only used once, disassembled and used for lumber when they reached their destination. The book is thick, not well organized, a scrap book collection, but was assembled at a time when primary sources were still available, which adds greatly to its value. It’s probably not a good introductory source, but a person who has some background in Salmon River history will find very interesting material. If you can find the book.

“River of No Return” by Johnny Carrey and Cort Conley (1978, Backeddy Books, Cambridge Idaho) is a mile-by-mile guide to the Salmon River from North Fork to the Snake River, focusing on history of the area. When it was published, there was very little information available about the Salmon River canyon. Though not a “how-to”, this book became a bible for boaters. Much additional information has become available since it was published. It has recently gone out of print. An update would be welcome.

Another classic of the Main Salmon is “The Last of the Mountain Men” (Harold Peterson 1969 Scribners), about Buckskin Bill Hart. Bill was undoubtedly the best-known of the Salmon River “hermits”. A trip on the Salmon River in the 1970s was not complete without a stop at Buckskin Bill’s, and even today, 40 years after his death, visiting his homestead is a routine stop. Bill enjoyed being a character, and Peterson’s book continues the theme. Interesting stuff, but prepare to do some filtering. Bill was known for making muzzle-loading rifles, and generally living as if it was still the 1800s. Educated, quirky. He knew a lot of Salmon River history, and I wish I had gotten more from him. Some thought him a phony, especially in his earlier years, but after 40 years you are what you are.

Bill had a nephew, Rodney Cox, who lived with him in the late 1960s and early 70s. Rodney, from the east, had a wife, Chana, and three little boys. Chana wrote a book, “ A River Went Out of Eden” (1992, LEXIKOS, Lagunitas, Co) that adds to the Buckskin Bill legend.

In the mid-70s a young fellow named Clifford Dean (“Mountain”) came to Salmon River and spent a couple of years with Buckskin Bill, who was nearing the peak of his fame. He recently gathered recollections, called it “Laughter in the Mountains”. The book provides some additional background on Buckskin. It’s a quick, entertaining read. www.authorhouse.com.

Doug Tims’ book about the Campbell’s Ferry area on the Main Salmon, “Merciless Eden “ (doug@rivertraveler.com) is another must-have. He has researched the history of the area in great depth, digging up a lot of previously unknown background about residents of the ferry. Prominent among them was Francis Zaunmiller Wisner, who lived there for over 45 years, until her death in 1986. Doug discovered a lot of material from her early life that she had intended to remain hidden. Doug is currently a co-owner of the Campbell’s Ferry property, so has a deep interest and background on its history, and also current issues affecting its’ preservation, including fires and agency policy. Doug is also owner of Maravia inflatable boats, Cascade Outfitters which is a boating equipment supply and catalogue in Boise, retired river outfitter on the Middle Fork and Selway, and past president of Idaho Outfitters and Guides Association and the national outfitter organization, America Outdoors. He and wife Phyllis spend the summers at Campbell’s Ferry, and welcome visitors there. Phyllis does a very good discussion of history of the site.

Another biography of Francis is “Haven in the Wilderness” by Carol Furey-Werhan, 1996. It lacks the depth of information that Doug was able to dig up.

“My Mountains–Where the River Still Runs Downhill” (Frances Zaunmiller Wisner, 1987, Idaho County Free Press, Grangeville, Id) is a collection of Frances’ newspaper articles, collected and published after her death. She was opinionated to say the least, and her articles need to be read in that light, but still there is a good deal of insight to living in the back country.

Harold Thomas, who owns Allison Ranch on the Main Salmon, has done an autobiography, “Pilot with a Purpose”, available at Orders@Xlibris.com. Harold is one of the founders of the Trus Joist corporation based in Boise, but has had a strong interest in the back country and flying. The book is a very interesting account of an up-by-the-bootstraps life and the building of a major corporation, and Harold‘s intense religious faith.

A couple of important books arrived in late fall of 2020. Polly Bemis has long been an important figure in the culture of the Main Salmon. There have been numerous accounts of her life, including books and films. Most have been wildly romanticized, beginning with the legend that she was table stakes in a poker game in Warren in the late 1800s. Priscilla Wegars has studied Polly’s life for many years, and this fall Polly Bemis: the Life and Times of a Chinese American Pioneer was published. Working with limited documentation, Wegars has thoroughly detailed and footnoted what is known about Polly’s life, discounting much of the nonsense, including the poker legend. This seems to be the defining source. Much of what is known of Polly’s life on the Salmon River is from Charlie Shepp’s diary, so to some extent the book also becomes a partial history of Shepp Ranch. Some people become legends because of noteworthy accomplishments—in the Salmon River, Guleke and Bob Smith come to mind, and Buckskin Bill for his eccentricities. Polly apparently was regarded as an exotic—Chinese woman, bound feet, living in the back country for decades—and, with a pleasing personality, was well-liked and respected. Just being Chinese was not unique at the time; the population of Idaho was about a third Chinese in 1870, and was especially high in the mining communities in and around the back country. But there weren’t many Chinese women, so there aren’t many Chinese in Idaho now. There are interesting references to boats coming down river, including Guleke. Also interesting is that among the diary detail of deer and fish harvested, skunks and rattlesnakes dealt with, there is no mention of elk—at least in the excerpts in this book. I haven’t had the chance to read the complete diaries.

Another legendary figure in the upper Salmon River country was George Shoup, who migrated to Colorado in the late 1850s gold rush, then in the early 1860s went to Virginia City, Montana, and then to what became Salmon immediately after the 1866 discovery of gold at Leesburg, just west of Salmon. Shoup was not a miner; he made his fortune supplying miners, though he did some investing in mining ventures. He immediately became a very influential figure in the development of the Salmon valley. He had stores in Salmon, Challis, Loon Creek during the short gold boom there in the early 1870s, Yankee Fork in the 1870s. He had extensive ranching operations in the Salmon area. He became a community leader, then became a state figure, eventually becoming US senator when Idaho became a state.

One of his sons, George E. Shoup, who was born about 1870, began a history of Lemhi County, published in installments in the local newspaper about 1940. The installments were gathered and published in a thin paperback. He apparently intended to revise and expand his history, but didn’t get it done. It remained a primary source for local history, though. Mike Crosby (who worked on our crew in the early 80s) and Terry Magoon, who were high school history and English teachers in the Salmon high school, have assumed the revision. They have added to Shoup’s work, providing a great deal of additional detail and perspective. It is an essential source for anyone interested in how this region developed. (Shoup’s History of Early Lemhi County –Crosby and Magoon, Lemhi County Historical Society.) There are chapters on river history, Indian history, early back-country travel, etc.

A common theme between these books is how remote Central Idaho was in the settlement period of the late 1800s. Polly lived a long days horseback trip from the closest communities, Dixie and Warren. But Dixie and Warren were the hind end of nowhere, accessible only by horseback for many years before crude and seasonal wagon roads were created. The Shoup book expands on this isolation. Salmon was on the edge of the mountain country, rather than in it, and was accessible by wagon from eastern Idaho—but with great expense and difficulty. Transportation costs brought many prices surprisingly close to current prices—without factoring an inflation of 25-30 times. A hundred dollars a ton for hay was frequently mentioned in back-country accounts–$2500-$3000 per ton in today’s dollars. I pay $150 now, and not so long ago paid $90-$100. But consider the difficulty of moving the hay to where it was needed. A nickel a pound was a common rate of freight for any goods, sometimes less, sometimes more, depending of course on distance and terrain. That would be more than a dollar a pound today. Lumber was a major issue, when transportation was all by horse or oxen. Logs had to be sawn into boards locally. Fourth of July Creek was a major source of wood in the early days, at least a days travel by wagon from Salmon each way. And consider firewood, the only source of heat and cooking in the town of Salmon, a number of miles by wagon from a supply of wood except for a limited amount of cottonwood along the river. Gold was the basis of the economy of the valley; nothing was exported from the valley except gold. Local logging could only supply local needs. Early crops were used in the community. Later, livestock could be driven from the valley for sale, but earlier the local mining camps were the only market. A stagecoach ride to the railroad—after it arrived in eastern Idaho—cost a weeks wages. The good old days were damn hard.

Reho Wolfe and her family came to the Salmon River in the 1940s. In the late 50s, she acquired a cabin at Rhett Creek, and maintained a seasonal residence until her death there in 1998. Her kids still have an arrangement with the Forest Service to occupy the cabin. She was one of the major personalities of the Salmon River, and was personally involved with many others—Andy the Russian, Monroe Hancock, Frances Zaunmiller, Buckskin Bill, and endless others. Her kids are the repositories of this history. “Reho Wolfe—The End of a Salmon River Era” by her son John Wolfe (2002, Rhett Creek Publishing) summarizes her life.

Many people came to Salmon River and never left. “Spirits of the Salmon River”—Kathy Deinhardt Hill, 2001 Backeddy Books Cambridge Idaho, is a list of grave sites along the Salmon River, with brief biographies.

For Salmon River residents from Allison Ranch to Shepp Ranch, Dixie was the closest town. “Gold at Dixie Gulch” (Marian Sweeney 1982 Clearwater Valley Publishing Co, Kamiah, Idaho) is not directly focused on Salmon River, but has a lot of information about river activities. It’s out of print, so if you come across a copy, grab it.

For the Middle Fork, a standard is Conley and Carrey’s “The Middle Fork-A Guide” (Carrey and Conley, 1992, Backeddy Books, Cambridge, Id). It’s a mile-by-mile history of the Middle Fork in the same format as their “River of No Return”. The first edition was 1977; this is the third version, with significant additional detail.

“Innocent on the Middle Fork” by Eliot DuBois, (1987, The Mountaineers, Seattle, Wa) is an account of his solo trip on the Middle Fork in 1942. Few people had floated the Middle Fork at that time. It is an adventure story, with the addition of descriptions of individuals living along the river that he stayed with overnight.

Johnny O’Connor, born about turn of the century, grew up along Panther Creek on the east boundary of the current River of No Return Wilderness area. “Rocky Mountain Treasures” (1992 Maverick Publications, Bend Or) describes his lifetime primarily between Panther Creek and the Middle Fork up until the late 1900s. There is a lot of detail about various events, individuals, and living conditions. Among other topics is discussion of the transplant of elk into the Panther Creek area in the ‘30s. Few people realize that elk were essentially absent from the area at the time. This book will be hard to find, but well worth the effort.

A couple of books add to background of the Lower Salmon area. “Whispers from Old Genesee and Echoes of the Salmon River” by Platt (1975, Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Wa) describes early-day ranching along the Salmon River. Platt arrived in the Salmon River canyon in 1895, established a ranch and raised a family. In those days cattle were wintered in the canyon and moved into the higher country for the summer. Families followed the cattle, often living in tents for the summer. Kids rode in panniers on pack horses. There were a number of residents along the river a hundred-odd years ago, scratching out a living with livestock and mining. Now the canyon is mostly empty, with some livestock still being wintered in the canyon, moving to the high, cooler, country in the summer. This book is a good insight into life along the Salmon at the time.

Platt’s son Kenneth (“Salmon River Saga”—Kenneth Platt, 1978, Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield Wa) also recorded his memories of growing up on the canyon ranch in the beginning of the 20th century. These two books provide a great insight to everyday pioneer life in the Salmon River canyon.

A couple of years ago I mentioned Dave Helfrich’s passing and the expectation that there would be a biography published. Dave’s dad was a guide in Oregon beginning in the 1920s, was among the first people to take a boat down the Middle Fork, just before WWII. Dave first ran the Middle Fork in 1948, at 16 years old—the year I was born— and developed an outfitting business on the Middle Fork, specializing in drift boats. Dave’s son and now granddaughter are currently running that business. As Dave was in his final, extended, illness, his family urged him to record his life. The result is the book, “Around the Campfire with David Prince Helfrich”, which is primarily a transcript of the recordings, available at davehelfrich.com.. The stories are Dave’s own words. The book should be on the shelf of anyone interested in river history.

“Bound for the Back Country–a History of Idaho’s Remote Airstrips” by Richard Holm, boundforthebackcountry@gmail.com, is much more than a listing of landing strips of central Idaho. Because aircraft have been so essential to access and activity, history of the whole region is interwoven through the book. For the student of the Idaho wilderness, this book is a must have. I can’t imagine how he gathered all the information, but I’m certainly grateful that he did. 550 large pages of pictures, personalities, histories, and locations. This is one of the standout contributions to the literature of the central Idaho wilderness area. It has been revised (2013) and updated based on input from the first edition, and is available in paperback.

Dick Williams came to Salmon in the late 1970s to fly the back-country, and became one of the best. Eventually he was flying corporate jets. “Notes from the Cockpit” is a review of his years of flying and back-country experience. For anybody with an interest in the topic, and Idaho’s back country in general, this book is a must.

“Against the Torrents” by Richard Ripley (Backeddy Books, Boise, Idaho) is a biography of Darrell and Rusty Bentz, who grew up near Whitebird, Idaho, and became legends in operating jet boats, running on-and-beyond-the-edge rivers in Idaho and other countries and continents. It is hard to imagine how a person could squeeze so much adventure into a life. Darrell built a very successful business in Lewiston designing and manufacturing jet boats, which is now operated by his son. After years of significant health problems, Darrell passed in about 2016. He will be missed. Darrell was one of the world’s nice guys. Just to visit with him, there was not a hint of the remarkable things he had done. This book was an eye-opener to me.

Jim and Holly Akenson spent a number of years at Taylor Ranch on Big Creek, a dozen miles up from the Middle Fork The Akensons have written of their time there in “7003 Days: 21 years in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness”, available at Caxton press.com. During the fire of 2000, they evacuated the Taylor Ranch, headed for the Flying B on horseback, and arrived in time to endure the fire that burned over the Flying B. A description is included in the book . Taylor Ranch was the homestead of Dave Lewis, a well-known cougar hunter who was a scout during the Sheepeater Indian war of 1879 and then returned to the area, remaining until his death in 1936. Pat Peek has written a biography of Lewis, “Couger Dave, Mountain Man of Idaho” 2004, Maverick Publications, Bend, Oregon. The homestead was the site of one of the battles. It was eventually acquired by the University of Idaho, and is used as a research center, particularly on mountain lions.

“Anything Worth Doing”, by Jo Deurbrouck, www.anythingworthdoing.com, is about the life and death of boatman Clancy Reese. Clancy had been a boatman on the Salmon River for many years, and died during a high-water distance record attempt a few years ago. The author worked as a boatman for several years, so has a feel for her material. In addition to the details of the final accident, there is good description of Clancy the individual. The book is very well-written.

“Mountain Scouting–a Handbook for Officers and Soldiers on the Frontiers” by Edward Farrow was originally published in 1881, reprinted by the University of Oklahoma Press. Farrow was involved in the Nez Perce war in 1877, the Bannock war in eastern Oregon and southern Idaho in 1878, and then the Sheepeater war in the Salmon River country in 1879. He apparently was in command of the unit that finally obtained a surrender and ended the war, in Cottonwood Meadows. Born in Maryland, Farrow was only 24 years old and three years out of West Point at the time of the Sheepeater campaign. The book is a “how to” for operating in back country, and incidentally has a few specific references to his time in central Idaho. It was published only a couple of years later. It is interesting for the references to the Sheepeater war, as well as the overall insight into the military procedures and life of the time. It contains some practical information, and some nonsense, is tedious in places, seems long on theory in places. Given Farrow’s age and experience at the time, I strongly suspect that a lot of the material was “borrowed” from other sources–probably from an 1859 book called “the Prairie Traveler“, written by another army officer. There is some word-for-word plagiarism. Yet, some of his comments seem remarkably fresh, personal, and accurate.

“When Skins Were Money: a history of the fur trade” by James Hanson, 2005, published by the Museum of the Fur Trade, museum@furtrade.org,will be useful to anyone interested in the early history and exploration of the frontier, including what happened in the Salmon River country. It discusses what happened, why it happened, where it happened, and who did it in a very readable manner. His viewpoints aren’t always politically correct, but that doesn’t detract from his insight.

A book new to me, though it has been out for 15 years, is ”One Vast Winter Count” by Colin Calloway. It deals with cultural changes among the Indians prior to the 1800s, with emphasis on the Northeast, Mississippi drainage, and the Southwest—not too much about the Northwest. Much of the background for the pre-Columbian era is inferential, and he also presents tribal traditions. Calloway also has done an extensive literature review of early explorers and Spanish administrator’s documents to describe events. The list of citations runs 130 pages. While the impact of the development of agriculture pre-Columbus, and then the introduction of disease, horses, guns, is vaguely understood by many people, many people have a general perception of Indian life before the mid 1800s as an ideal, uncorrupted, existence, in balance with their environment. This book describes the inter-tribal wars for territory, resulting tribal migrations and displacements, continual raids for food and slaves, extermination attempts, politics among the tribes attempting to adapt to the coming of various European nations, trade relations among the tribes, as well as the interactions of the competing European powers. It is significant to remember that the image many people have of Indian on horseback living on buffalo was a very brief period. It was only about 150 years from the time the Indians got horses until they were put on reservations. It was hell to be an Indian during the mid to late 1800s, with broken treaties, reservations, and forced cultural change. It was also hell to be an Indian during the preceding three centuries—and we really don’t know much about why cultures like the Anasazi collapsed before European influence, but conditions must have not been pleasant.

The local library was closed or limited access throughout the spring of 2020, so I began rereading my own shelves. Periodically I need to refresh my memory of the various histories. An advantage of being a geezer, though, is that now I can reread and enjoy fiction that I read long ago, cannot remember “who did it”. One author I rediscovered was Andy Russell. I greatly enjoyed his “Trails of a Wilderness Wanderer” that was on my shelf, and then some of his others through interlibrary loan. Russell was born in 1915 in southwest Canada, second-generation homesteader family, a very skillful writer, remarkably so considering his limited formal education. He was a rancher, hunting guide, and later became a photographer, writer, and lecturer, achieving recognition primarily in the 1960s. His descriptions of living on the edge of and in wilderness provide insight to a later stage of the homestead era. He celebrates the magnificence of the back country and its wildlife in its original condition, in an era that cannot be recovered—and mourns the impact of road penetration during the 50s. His time was primarily in southwest Canada, but did spend a little time along the Salmon, horse packing with Bill Sullivan.

I came across a recent book (2015) that will be important to anyone interested in regional history—Inland Salish Journey: Fur Trade to Settlement, by Mike Reeb, Keokee Books, Sandpoint, Id, KeokeeBooks.com. The focus is on northern Idaho and southwest Montana, especially the Bitterroot valley of Montana, and the Flathead Indians there, with reference to kindred tribes including the Nez Perce. The author has done a tremendous amount of research about his obviously favorite tribe of Indians, describing everyday life as well as personalities of leaders, interactions with other tribes, white trappers and settlers, US government, and changing conditions during the transition period of the mid-1800s. Takeaways include the large amount of intertribal conflict and horse-stealing raids, especially by the Blackfeet (who didn’t seem to get along with anybody), the low population density and the amount of travel by these Indians, and the great progress these Indians were making toward changing times, including growing crops and livestock, by the 1850s and 60s. There was apparently much more of a Nez Perce and Flathead presence here in the Lemhi Valley than I realized. I was under the impression that this was pretty much exclusively Shoshone country, but not according to Reeb. The Lemhi and Salmon River country is on the fringe of the focus of this book, but it helps to understanding what was going on here at that time. There is also interesting description of the decline of the buffalo herds in western Montana and Idaho in the mid-1800s, well before the commonly-known destruction of the buffalo herds on the Great Plains after the Civil War. (picture of buffalo) Indians were in this area for 10,000 years—but it is important to realize how brief was the horse culture that most people associate with the Plains Indians. From the coming of the horse to the reservation era was only a hundred fifty years—little longer than we have had cars. Horses, then guns, created intertribal turmoil that preceded the invasion of white settlers. The 1800s were terrible years for Indians—and not very good for most whites, either, in the robber-baron era. This is one of the best books I have come across about the transition period.

“Wilderness Brothers–Prospecting, Horse Packing, & Homesteading on the Western Frontier”, by Wayne Minshall, available streamside scribe@gmail.com, is an editing of the diaries of Luman Caswell, who was prospecting and homesteading on Big Creek off the Middle Fork in the 1890s. The result was the short-lived gold rush–the last in the US–at Thunder Mountain that peaked in 1902, with a significant impact on the Salmon River country. There is a lot of detail about how the Caswells came to be in the Big Creek country, how they developed their homestead and claims, how they lived. There were three Caswell brothers and a couple of partners, who sold their claims to a developer for a significant sum before the whole thing fizzled out. They were all well off for 20 years, prosperous businessmen and stockmen–and all went broke in the 20s and died in poverty. The depression of the 30s is part of the national culture, but the 20s were tough in agriculture. There was a boom during WWI, ag prices inflated, land prices followed, and after the war the bubble broke. Hard times hit here well before the 30s. Another interesting point was the comments on wildlife. Trapping was an important part of the Caswell’s economy in the early 90s as they were getting started. While there were many references to deer, there were very few to elk. The frequent encounters with mountain lions and wolves was remarkable. Very interesting read.

A few years ago , retired river outfitters Dick Linford and Bob Volpert published “Halfway to Halfway”. It is a collection of stories written by boatmen–not we-almost-died stories, but a variety of experiences over the years. Daughter Stephanie has a story in it. Available from halfwaypublishing.com. Just the thing for winter evenings. A sequel is “Halfway to Halfway and Back”, this time mostly by Dick and Bob, but some by other boatmen. Mostly the stories are about the screwball things that happen in the business—the kind of stories that are told around a campfire with the encouragement of a little tongue-loosener. There is rumor of yet a third in the future.“

Available again is “Murder on the Middle Fork” by Don Smith, through his daughter Heather Thomas, at hsmiththomas@centurytel.net. Don was a minister in Salmon for many years, with a deep interest in the back-country. The story is based on the murder of Jake Reberg in 1917 at Sheep Creek on the Middle Fork of the Salmon. In Don’s notes, he says “…Our arrival (in Salmon) was less than 30 years after the murder….the story had been told and retold so many times by so many people with different opinions that sometimes it was hard to believe they were talking about the same thing”. Don used the various stories to piece together a romanticized version that might be as accurate as any. One of the primary participants in the aftermath lived across the street from us for a while in the ‘80s, and I got to hear his story–but wish I had asked more questions. He claimed to have packed Rebergs’s body out of the back country.

Tony Latham, who ran a boat for us a season or two in the late 80s, then became an Idaho game warden, wrote a true but pretty dark story about one of his major undercover poaching cases on the fringe of the Idaho wilderness, dealing with a side of people that nobody should have to see (“Trafficking–a memoir of an undercover game warden“, tony.latham@gmail.com). It is is not directly a Salmon River book, but deals with an issue of back-country areas–poaching game animals. Serious, commercial, poaching often requires undercover, “sting”, investigations to get convictions, which Tony became involved in. Fish and Game violations can range from incidents due to ignorance, confusing regulations, inattention to detail, poor judgement, excitement, frustration at the difficulty of a hunt, and bad luck, to increasingly deliberate greed and disregard of ethics of hunting, to just plain no-good sons of bitches that disregard all basic rules of civilized behavior. This book deals with one of Tony’s investigations of the latter. Well-written, and an eye-opener to a sub-culture. He has also written a fiction/thriller (“Five Fingers”) with a setting in the Challis area, upstream from Salmon. Beyond the suspense plot line, the book provides a bit of insight into the routine of a game warden. Another is “Behind a Thin Green Line” (2017), a non-fiction book about his efforts to stop a group of elk poachers operating in the Pahsimeroi Valley southeast of Salmon. It is of particular interest to me because I did my thesis work on antelope in this area in the mid-70s. At the time I was spending time in the valley, there were not enough elk there to have an elk poaching problem. Tony has another novel, “Seven Dead Fish”, with a setting in the Challis, Idaho, area, featuring a game warden who stumbles into a nasty but not implausible situation. Available at tonylatham@gmail.com.

Another novel with a Salmon River setting is “Antlers of Autumn” by Larry Gwartney (larrygwartney515@hotmail.com). Larry’s family had a traditional elk hunting camp in the high country near Salmon. The book traces a boy’s growing up through the elk camp setting. Another of Larry’s novels is “Reflections in the River of No Return“. It’s fiction but told as personal escapades while growing up in Salmon, then a boatman’s story of a Middle Fork trip of the “No S…, I Was There” category– and written so that you will feel you were there, too. “The Ballad of China Lee” describes life and prejudices in Salmon in the early ’30s. When I came here, Salmon was very homogeneous, but it wasn’t always so; there was a small Chinatown, the Indian camp, recent European immigrants, Basque sheepherders. Larry’s detail and style rings as true as the anvil in his dad’s blacksmith shop. Larry is a retired English teacher, from a very colorful Salmon family. His dad was a great story-teller, and his uncle Jack was better; unfortunately I was too late to know his grandpa, who was even more of a legend. Larry boated a few trips for us in 80‘s, taught in the Salmon high school with Peg for a career, good campfire guitar and dutch oven hand.

Another book, by well-known California river outfitter William McGinnis, is “Whitewater–a Thriller” available at WhitewaterVoyages.com/books, or Sue@WhitewaterVoyages.com–or 800-400-7238. The book is adventure fiction, set on the Kern River in California–not the usual subject of this list, but a novel with a river setting is interesting entertainment. There is some good description of paddle boating, and a bit of description of California guide culture. McGinnis has written several how-to whitewater books over the years, partly through training boatmen for his large day-trip business in California.

“